Climate change is likely to devastate our planet, says Snøhetta co-founder Kjetil Trædal Thorsen. In the second part of an exclusive interview, he tells Dezeen it is “absolutely possible” to create fully CO2 negative buildings.

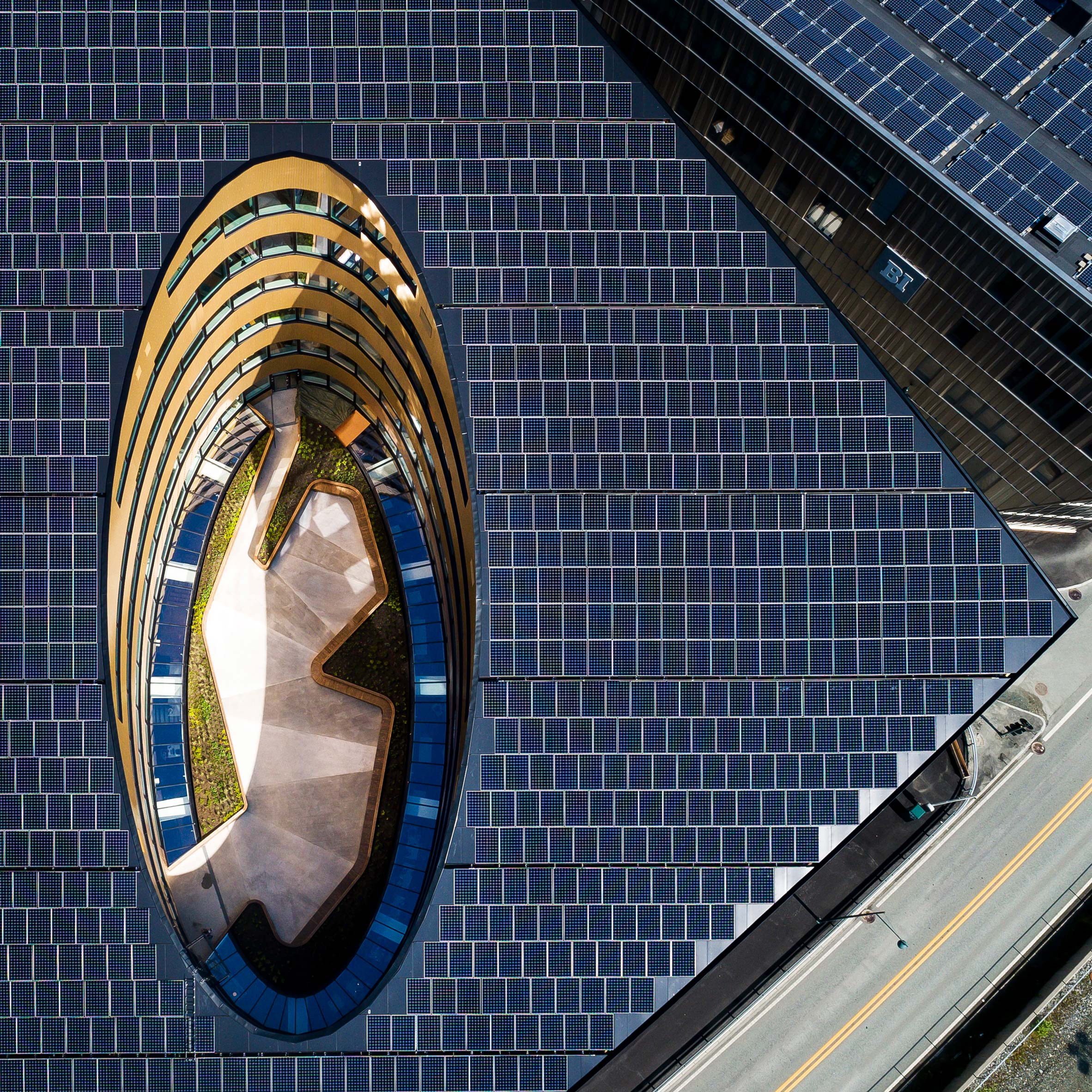

Snøhetta is a pioneer of eco-friendly architecture, with projects including Powerhouse Brattørkaia, which produces twice as much energy as it consumes, and ZEB Pilot House, which produces enough power for itself and an electric car.

The firm also recently pledged to make all its buildings carbon negative within 20 years.

“It’s all on the market and it’s not even particularly expensive,” said Thorsen. “So it’s absolutely possible to get fully CO2 negative buildings calculated over a clean energy production period of four years.”

However Thorsen said that, in spite of these breakthroughs, it is unlikely that the building industry will be able to change fast enough to reverse the impact of global warming on the environment. Construction currently contributes 40 per cent of global carbon emissions.

“There are some certain armageddon situations when it comes to this whole thing,” he said. “That’s really serious.”

“Adaptive design for a failed future”

According to the landmark IPCC report published last year, big changes need to be implemented around the globe by 2030 in order to limit the global temperature rise to just 1.5 degrees celsius.

Thorsen believes that, as things stand, the most likely outcome for the planet will be a rise of three or four degrees. This would result in food and water shortages, flooding of coastal cities and an irreversible loss of biodiversity.

He believes architects and designers need to use their skills to prepare for life in this new reality.

“We’re more likely looking at four degrees,” he said. “The ecosystem and the ecological barriers when it comes to wildlife and human life in all of these situations is something that we need to plan for.”

“We need to plan for a default situation,” he continued. “It might be adaptive design for a failed future.”

New challenges for architects

Thorsen believes there will be new challenges facing architects in a climate-change future. He suggests that, with agricultural land threatened by flooding, food production might become an essential component of new buildings.

“We’ve done studies on the embodied energy of soil,” he said. “Nobody recognises embodied energy and its relationship to food production. That needs to be part of the calculation as well. How do we consume and what type of consumption is it?”

The architect doesn’t believe there will come a time when new buildings aren’t required at all. He points to the Munch Museum, currently under construction in Oslo, as an example of a new building that is necessary.

“I don’t think we will be in a situation where we’re not constructing,” he said, “but I do believe that we have to be extremely precise when it comes to the footprint of the things that we’re creating.”

“We have to be extremely precise”

“There are certain things you will not get away from,” he continued. “The question about a new Munch Museum, for instance.”

“If you cannot store these paintings safely in what is existing, you have to build a safe museum, if you want them to be seen by people 200 years down the road.”

Snøhetta celebrates its 30th anniversary this year. To mark the occasion, Thorsen also spoke to Dezeen about how the firm’s ultimate aim has always been to make buildings for the betterment of society.

The studio’s portfolio includes the Oslo Opera House, which famously has a plaza on its roof, and the National September 11 Memorial Museum Museum in New York.

Read on for an edited transcript from the second part of the interview with Thorsen:

Amy Frearson: Can you tell me about how environmental sustainability has come into your work?

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen: There has been this kind of transition in the position of architecture. We had the development of star architecture, which was really important to lift the standing of architecture. But it can’t be the only way forward when you think about providing for the next generation. This led us from thinking about social sustainability into environmental sustainability.

I think now we are one of the best offices to understand what real CO2 negativity means. We calculate everything, so we know how much CO2 there is in the whole construction.

Amy Frearson: Do you do that in every project?

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen: Not every project yet, but many of them now. We have finished three and we’re continuing with another four. The Powerhouse definition is, for us, at the core.

It looks like we have to produce between 50 and 60 per cent more energy than we consume from day one

So now, with environmental and social sustainability, the environmental is finally now coming on top of the circle for us. It has to merge, in a way. You cannot leave one simply by adding the other. You have to understand that it’s not project by project that we actually live from, the singularity of project by project. We live from the totality of the projects. So you learn something here and learn something there and you start putting it together.

The Powerhouse model is not in any way perfect yet, when it comes to dealing with these things. But it will be.

Amy Frearson: What impact will this have on the way you design?

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen: We don’t know exactly how it will affect the understanding of aesthetics, but they will change. We will see other definitions of typologies, it’s certain.

Amy Frearson: Are there any particular techniques or materials that you think Snøhetta will push away from?

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen: As I said, we need the overviews of the materials and their CO2 equivalents. If the stainless-steel screw that you’re using is produced on coal or water power, it will have a different CO2 footprint. We have to know the whole value chain of the products. Then we have to know how much it takes to recycle them with an assumed type of recycling method. Only then can you have a full overview of the CO2 footprint of a building, from cradle to cradle, and know how much clean energy you have to produce. With the standard of the building world right now, it looks like we have to produce between 50 and 60 per cent more energy than we consume from day one.

Amy Frearson: Do you think that’s possible on a broad scale?

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen: Yes. What is astonishing is that, for the Powerhouse Brattørkaia, we didn’t need to invent anything. It’s all on the market and it’s not even particularly expensive. So it’s absolutely possible to get fully CO2 negative buildings calculated over a clean energy production period of four years.

We have to reduce our freedom and choice when it comes to materials

When you’re using old buildings, you don’t have to calculate in because it’s already been written off in the large CO2 calculation. So then we can reduce the time span for becoming really CO2 negative. So it’s absolutely possible.

Amy Frearson: There’s clearly a lot of complexity in the process. That could be an obstacle when it comes to encouraging more architects to adopt sustainable practices?

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen: I totally agree. In a way, to be able to deal with these things, we have to reduce our freedom and choice when it comes to materials, for instance.

We spent two and a half years convincing the Saudis to use rammed earth [for the King Abdulaziz Centre for World Culture], because it wasn’t glossy. It’s not really contemporary, it’s old. But to do that in 2008, and really push that forward at a scale that had not been seen in Saudi for 1,000 years was, in a way, a statement for us, to reinterpret the ground of where the building was standing and use the ground to actually construct the building. With the stainless steel pipes, we had enormous high-tech and very low-tech combined in the same building. We actually started that idea in Alexandria, where we had a really high-tech aluminium roof protecting against the light and hand-made granite from Aswan, which is how the Egyptians have been dealing with their storms for thousands of years.

Amy Frearson: Do you think we will reach a point where sustainable architecture becomes less about making new buildings and more about just dealing with the structures that we already have?

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen: I do love that perspective. I was part of the jury that chose degrowth as the theme for the Oslo Triennale. But that perspective is a western point of view and it doesn’t count for the whole world. You cannot talk about degrowth to someone who lives on $1 a day. It’s not possible. There is an uneven distribution of welfare and goods worldwide, as well as knowledge and education. So I don’t think we can transfer this completely to everything that is happening around the world.

The next thing to think about is, what happens if we don’t reach our climate goals?

At the same time, we cannot make the same mistakes. So the focus is on this further development of whatever is the big problem. We’ve made a choice, we’re saying the greenhouse effect and climate change, in accordance with many other scientists, is the biggest challenge for the moment. So that means we need to focus on the CO2, because the building industry is contributing 40 per cent of the climate emissions.

But there are certain things you will not get away from. The question about a new Munch Museum, for instance. If you cannot store these paintings safely in what is existing, you have to build a safe museum, if you want them to be seen by people 200 years down the road.

I don’t think we will be in a situation where we’re not constructing, but I do believe that we have to be extremely precise when it comes to the footprint of the things that we’re creating.

The next thing to think about, which is maybe just as interesting, is what happens if we don’t reach our climate goals? How will we as architects and designers relate to these new conditions? It might be adaptive design for a failed future where people are still going to be around, but maybe in different constellations, with climate-immigration issues.

Amy Frearson: Do you think that’s the more likely outcome? Are you pessimistic about our ability to stop climate change?

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen: Yes. I know we’re not going to reach 1.5 degrees [the Paris agreement temperature limit]. I would claim we’re not reaching the two degree limit, probably not even the three degree limit. We’re more likely looking at four degrees. The ecosystem and the ecological barriers when it comes to wildlife and human life in all of these situations is something that we need to plan for. We need to plan for a default situation.

Amy Frearson: That thinking aligns with the theme of this year’s Milan Triennale, Broken Nature, curated by Paola Antonelli. Its claim was that humans are moving towards extinction and that the most productive thing that can be done is to plan for that. Is that what you’re saying?

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen: I think it is crucial to say, for instance, we know our living conditions and the food situation on Earth will probably not work if global warming goes beyond five degrees. So there are some certain armageddon situations when it comes to this whole thing. That’s really serious. That breaking point could also be other things that we don’t know.

We are privileged but we have to use this privileged situation

For instance, the issue we’ve had with environmentally sustainable buildings is that a low CO2 footprint does not necessarily provide a healthy building. It can still increase asthma and other diseases. The fact that we’re spending 90 per cent of our lives indoors is coming in addition.

The other question is how we actually live together. All of these things are at the table at the same time.

Amy Frearson: You mention the global food crisis, which is something that architecture isn’t really addressing at the moment. After looking at how buildings can produce energy, should we be looking at how they can also produce food?

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen: Very correct. We’ve done studies on the embodied energy of soil. Imagine that we’ve spent 400 years creating agricultural soil, a 30 or 40 centimetre layer. People have been working that with their hands for generations. And then all of a sudden you build on it. Nobody recognises that embodied energy and its relationship to food production. That needs to be part of the calculation as well. How do we consume and what type of consumption is it?

We are privileged but we have to use this privileged situation. I’m more concerned about that than about not having a warm fireplace at home. I still need that fireplace. I’m not willing to move into a cave.

Of course there’s a lot research ongoing, but most building laws and regulations around the world are very slow in reacting to research results. As you know, the building industry is a big lobby of different production lines and products, and to some extent they have influenced the building regulations. So the building industry is partially embedded directly into what we’re allowed to do and not allowed to do. So I’m very keen on being able to do experimentation that you can actually measure outside of the legal boundaries. We need want one-to-one larger experimentation projects.

The post Architects must plan for “armageddon situations” says Snøhetta’s Kjetil Trædal Thorsen appeared first on Dezeen.